SBC Reflections

10 min read

Will Puckett

The world of single board computing is alive right now. Like Julie Andrews spinning on a grassy hilltop, if you're willing to go down the rabbit hole, you'll might come out singing. The 'chip shortage' of the past few years has left many people (myself included) a lot more willing to experiment than they might otherwise have been. Internet sentiment evidences a community that is a strange mix of excited, annoyed (the comments on this article), and somewhat unsettled. I can't wait to see what another year or two brings as people respond to what's going on in this space.

Over the past couple of months, I've been making upgrades that are a couple of years old. There's no front page news here—it's largely just that some things have come down a lot in costs (despite the general trend) and I needed a few new machines—but I thought it would be useful to collect and share my thoughts both for my own reference later and in the event that my traversal proves at all helpful for others grappling with similar decisions. Even with all the excitement, for me, the best sbc is still the one I can avoid purchasing, installing, and don't have to maintain. But for tasks that have to run locally, the rapidly improving state of affairs is much appreciated.

The Need for...

In terms of processor speed, I wish I had run across a project called sbc-bench much earlier. It's thorough listing of benchmarks was incredibly useful for me as I started exploring rpi alternatives. It also has a listing of results sorted by speed that can simplify comparisons, depending on what information you're seeking. The a1.xlarge and M1 benchmarks really helped make the numbers relatable. I tend, like most people, I imagine, to want continuously more capable things in successively smaller packages. To that end, I wish it included information about the form factor of each board, but that in no way takes away from the excellent utility sbc-bench already provides, it's just me being lazy.

NVMe

My constant pain/gripe point with sbc's is of course their speed. As I tried to reflect more deeply on this, I realized that it wasn't so much the speed that my projects ran at (I was very happy using Klipper on a pi zero 2 for instance), but the speed at which my admin tasks ran. Taking several minutes to complete system updates, or even just to image the sd as I'm getting started with a new machine all felt like such a drag, and made me less productive. Essentially, I was running into a wall with disk I/O bound tasks.

In the past I had experimented with using usb thumb drives, but didn't really like leaving them hanging out of the pis. Their performance also tended to degrade with longer running tasks as they didn't dissipate heat well. I don't remember how I happened onto it this summer, but perhaps the biggest advance for me was exploring some newer drives for rpi. I had been testing a 1tb NVMe drive in a ssd enclosure which had to be connected via a powered hub, and I was enamored with the order of magnitude boost in disk bound tasks. It made my sbc start to feel like something I had never expected from it before: a real computer.

Naturally, I had to get rid of the hub. James Chambers, who's writing is essential reading for any one in the sbc space if you haven't happened onto it already, wrote an awesome piece that proved very useful for me: Best Working SSD / Storage Adapters for Raspberry Pi 4 / 400. I switched to an Orico GV100 NVMe SSD drive which the pi had no problems booting and operating via USB. It wasn't the cheapest drive, but I hastily thought it was perfect and bought a couple of them for my printers. I then made the mistake of continuing reading.

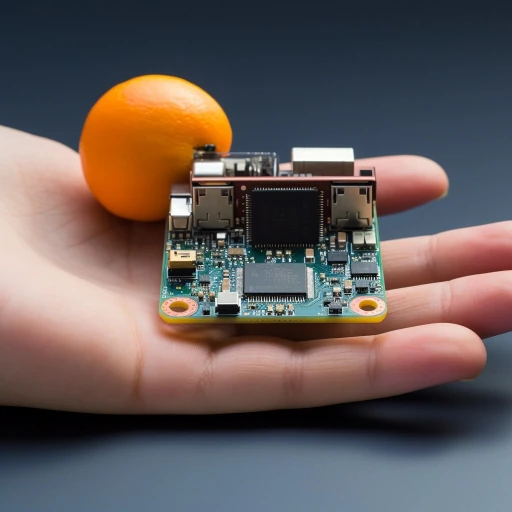

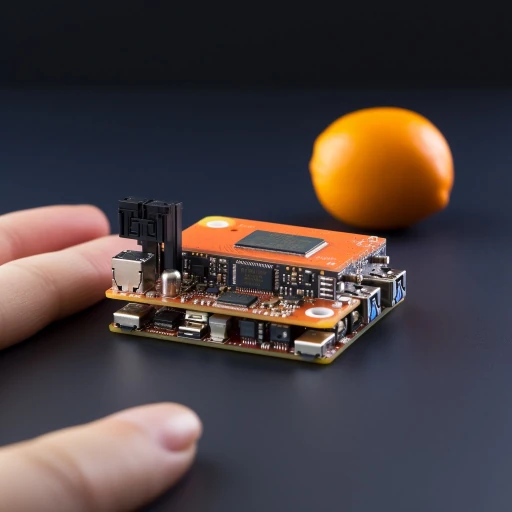

I had never worked with the CM4 before, but when I discovered it exposed the PCIe lane and could more than double the disk I/O speed of the drives I had been testing, I was interested. In the past when I had looked at the compute modules, I had been put off by what seemed somehow more complicated, as well as the high prices both of the modules and requsite carrier boards such as the tofu. As I tottered along in my traversal of all things modern pi, I happened on the WaveShare Mini Base Board (A). At just under $20 bucks, I was willing to try one, but I didn't think I'd be able to locate a reasonably priced CM4. Imagine my surprise when I found a 2gig CM4 on the WaveShare site itself—I was able to order the Base Board and the CM4 in a single purchase. Once they arrived I excitedly wanted to test them. The Mini Base Board only takes 2242 and 2230 drives, however, so I couldn't throw my 2280 1tb drive in it (or use a 2242 drive with modules on both side due to the 2230 mount). I was past the return window on the Orico drives so I decided to take the pluge with my dremel and remove the 2242 from the Orico case (I had looked at a take apart online and it seemed simple enough). Mine didn't want to come out of the case readily and I ended up having to destroy the usb to m.2 carrier board with a screw driver getting it out so I wouldn't recommend it, but I was excited to be all scientific and test exactly the same drive in the new enclosure.

It made my sbc start to feel like something I had never expected from it before: a real computer.

The NVMe drive performed exceptionally well, scoring an 18,500 on pibenchmarks.com with no overclocking (which can evidently further increase drive performance). I was truly delighted. Suddenly, my monthly update tasks would take mere seconds, while the tasks I actully used the pi for would continue running the same as always—largely unnoticed. It was perfect.

I did a little further testing with the CM4 disks. The CM4 doesn't have USB 3 (it exposese the PCIe lane for other use which allows the m.2, whereas the pi4b uses the PCIe lane for USB 3). As a result, the Orico drive over USB was much slower, running over usb-storage instead of uasp, and logging a paltry 3,095 in my pibenchmark test.

Overall, the CM4 turned out to be a great option for use with a single, 'internal' disk, but not a great choice for a machine that needs to be used with multiple/external usb disks.

CM4 Alternatives

I really enjoyed getting to know the CM4. The carrier board market has exploded over recent years, and benefitted substantially from the competition (especially from the consumer's point of view). I use the BTT Pico for my 3D printers, and the form factor of the Mini Base Board is ideal—I can mount it directly under the MCU with standard pi mounting holes. I adore the m.2 slot. As a user of Noctua fans, I'm also beside myself to have a full 4 pin fan port. Sure, it's easy enough to make a small adapter cable for the fans, but it's just one less thing to handle and I already spend an embarassing amount of time crimping little tiny cables.

I continued to dig. I kept hearing that pi alternatives had proliferated during the pandemic, and I wondered if I could find a more affordable better performing board. I tried the BTT CB1, but I hadn't read the documentation carefully enough before purchasing it: it doesn't have PCIe, and is therefore incapable of using the higher speed storage. I did find it pretty easy to download and setup the BTT provided images, but stopped after benchmarking the SD card.

I next tried the Core3566 module. Since the WaveShare baseboards were promoted to work with it, I thought I might be in luck.

Unfortunately, I couldn't get any of the LuckFox provided images to work. It was a little strange to be downloading them from a Google Drive file (!?!). They all errored out when I tried to use them with Etcher. I never got the Core3566 booted, other than in rom mode, which involved trusting the luckfox tool with sudo, not great. In all fairness, it may just be setup really poorly in terms of MacOS, and maybe I should try buring one of the images from an rpi, but, after a couple of hours I threw in the towel. It's probably worth another go 'round: although sbc-bench doesn't test the Core3566 itself, other 3566 processor based boards perform just shy of the pi4b/CM4.

𝜋 Π ϖ 𝚷 ℿ

Somewhere along the way, tumbling further and further down a seemingly bottomless hole of mildly to extravagently over-priced and under-powered hardware, I had an inkling that some newer hardware must be just around the corner. I scoured the rurmormills. All indications pointed to the Pi 5 not coming out till later next year. So naturally, later in the week after I had just been busy ordering more 3 year old CM4s and base board from China, news of the pi 5 struck. While it would have been easy to feel a sense of disappointment, I relegated myself to the understanding that it was more like when I give up on the bus and start walking and it immediately comes over the hill: that my giving up was the causality of the product drop.

It's easy to concede that the Pi5 is a good improvement over its predecessor, but I can't say that I'm enamored, at least on specs alone. Sure, doubling the processor speed (according to results on, you guessed it, sbc-bench) is a welcome change at a pretty low price bump from earlier models. But not including an m.2 slot on board is just a giant miss, especially considering that the last NVMe drive I purchased was cheaper than a comparably sized sd card ($9.99 for the NVMe disk vs $14.99 for the sd card on amazon).

While I'm also unhappy that the new pi still uses the bulkier usb a plugs, I'm even more upset at what's going on in the usb pd arena with the sbc market in general. For people who use sbcs to integrate with mcus, switching to usbc pd 3.1 is going to be a game changer. Being able to just plug toolhead and control boards into the usbc pd 3.1 port and have the sbc handle the power management side has to happen. Even if it didn't integrate pd 3.1, at least seeing the pi use something other than the god awful 5a@5v that it choose would be welcome. Yes, I know it's technically in the pd spec, but it's so uncommon it just doesn't seem like a good choice.

I was also hoping to see a solid PIO design on the Pi5, so I could do things like use CAN without having to suffer through the current adapter board situation. PIO is, for me at least, by far the most interesting thing Rpi has done to date. It's the feature that sets the company apart. I've been using it with Kevin O'Connor's CAN software and it's amazing. Even though the Pi5 does include some PIO functionality, it seems like it's a little more paired down and not as fully embraced as I would have hoped.

I get it, the Pi5 isn't really designed for me and my needs. It feels like it's made more to target retirees (think grandpad) and users in developing markets, and I can truly appreciate that stance. The world needs well performing machines at all levels. However, as someone who uses the pi exclusively headlessly, I would prefer less of an emphasis on graphics, and more focus on power management and I/O.

So it sounds like I need to keep waiting for the Rpi CM5 to drop. But if it specs out the same as the Pi5, I'd rather have the CM4 alternative everyone is anxiously waiting for: the Radxa CM5. If its core3588 is any indicator, it should perform at about 3 times the speed of the pi4b, and outpace even the new pi5 by 50%. I'm anxious to see how it's priced, but I'll probably have to try one.